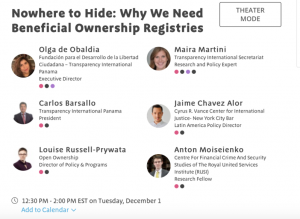

Nowhere to hide

7 de Junio de 2021

| NO HAY DONDE ESCONDERSE: ¿POR QUÉ NECESITAMOS REGISTROS DE BENEFICIARIOS FINALES? IACC 01 Diciembre 2020. Panamá: un caso de estudio Por Carlos Barsallo, presidente del Capítulo de Panamá de Transparencia Internacional En 2016, como reacción a los “Papeles de Panamá”, el Gobierno panameño nombró un comité de expertos independientes para evaluar las prácticas de los servicios del centro financiero de Panamá. El trabajo del comité fue: “dirigido a que el país lidere los esfuerzos de la comunidad internacional para construir una nueva arquitectura financiera global.” Lamentablemente, hasta ahora Panamá no ha liderado los esfuerzos de la comunidad internacional para construir una nueva arquitectura financiera global. Esto no significa que Panamá no haya estado haciendo cambios legales. Por el contrario, Panamá ha estado introduciendo cambios legales y algunos de ellos son -en teoría- buenos. Algunos cambios legales han sido aprobados muy rápidamente como una reacción a la presión externa y con un objetivo específico, ser removidos de la lista del Grupo de Acción Financiera Internacional de países con importantes deficiencias en la lucha contra el lavado de dinero. Esta forma pragmática de reaccionar al problema, en lugar de anticiparse y prevenir el problema, no ha dado tiempo para analizar y responder preguntas como: ¿qué quieres hacer?, ¿por qué lo haces? y ¿para quién lo haces?. Por eso este taller es relevante. Podría ayudar a otros con la misma lucha. Las preguntas que voy a responder en relación con los registros de beneficiarios finales son el cómo y el cuándo, utilizando algunas lecciones aprendidas hasta ahora del caso panameño, que aún es una labor en curso. Primero algunos antecedentes. Abogados panameños y conoce a tu cliente. La obligación de los abogados panameños de conocer a su cliente actuando como agentes residentes en sociedades anónimas panameñas, existe legalmente desde 1994, es decir, desde hace más de 25 años. Inicialmente, se limitaba al tráfico de drogas. El cumplimiento, la efectividad y la eficiencia no han sido debidamente medidos por las autoridades panameñas, el sector privado o la academia. Los diferentes gobiernos siempre han insistido en que la legislación y la práctica eran adecuadas. Las evaluaciones internacionales indicaron lo contrario. Hasta hace muy poco, no hemos tenido datos oficiales locales (a través de la evaluación nacional de riesgos) que nos permitieran evaluar si en alguna ocasión en la que los agentes residentes han tenido que informar, local o internacionalmente, de quién es el beneficiario de la corporación o fundación de interés privado, esto se ha hecho oportuna y adecuadamente. Esta sola omisión y demora dicen mucho. Tengo buenas razones para creer que las fórmulas jurídicas desarrolladas durante los últimos 25 años, en particular las relacionadas con las obligaciones de los agentes residentes, no han funcionado correctamente. Ello se debe a una combinación de factores que van desde su deficiente formulación, a veces intencionada, hasta la palpable falta de voluntad de aplicarla estrictamente. El siguiente es un punto clave: Cualquier abogado panameño puede ser un agente residente. Sólo los abogados panameños, o las firmas de abogados panameñas, pueden ser agentes residentes. Según el informe de la Evaluación Mutua de Panamá del Grupo de Acción Financiera Latinoamericana de enero de 2018, había cuatro mil abogados y trescientos bufetes de abogados registrados como agentes residentes ante el regulador panameño de Sujetos No Financieros. Es importante considerar que según datos de la Corte Suprema de Justicia de Panamá, en 1994 había tres mil abogados registrados con idoneidad. En el año 2020 el número de abogados con idoneidad supera los veinticinco mil. La ley específica que trata de la obligación de los agentes residentes panameños de conocer a su cliente es la Ley 2 de 2011. Ha sido enmendada 3 veces. Esta ley contiene ciertos artículos que, en mi opinión, contradicen los objetivos de la ley contra el lavado de dinero. Por ejemplo, crea un espacio para interpretaciones en temas importantes como el deber de reportar actividades sospechosas y procedimientos de debida diligencia por parte de los abogados. Esto ha creado problemas cuando se ha evaluado a Panamá. El resultado hoy es que el Grupo de Acción Financiera Internacional ha identificado a Panamá como una jurisdicción con deficiencias estratégicas contra el lavado de dinero. Panamá es una jurisdicción sujeta a la supervisión del Grupo de Acción Financiera Internacional. Por si lo anterior no fuera suficiente, la fuerza mediática de la labor periodística de investigación puesta a disposición del mundo, destacando entre ellas los Panama Papers, ha hecho imposible que Panamá no reaccione con cambios que se ajusten a las nuevas realidades y necesidades de transparencia. El efecto de los Panama Papers puede verse claramente no sólo en la disminución de nuevas incorporaciones sino en el aumento de las disoluciones de sociedades anónimas panameñas. Por ejemplo, si se compara el año 2009 con el año 2019, la disminución sustancial es evidente. En el año 2009 se incorporaron treinta y ocho mil sociedades anónimas panameñas. En 2019, se constituyeron catorce mil sociedades anónimas panameñas. En 2014 se disolvieron mil sociedades anónimas, mientras que en 2018 se disolvieron doce mil sociedades anónimas. Ante la incesante presión internacional, y ante los insatisfactorios resultados de la última evaluación internacional, la Asamblea Nacional de Panamá aprobó el 17 de marzo de 2020 la Ley 129 presentada por el Órgano Ejecutivo mediante la cual se crea un Sistema Privado y Único de Registro de Beneficiarios Finales en Panamá. El sistema privado y único de registro de los beneficiarios finales. El propósito de la nueva ley es crear un sistema único de registro: “para facilitar el acceso a beneficiarios finales de las entidades jurídicas reunidas por los abogados que prestan los servicios de un agente residente para ayudar a la autoridad competente en la prevención del blanqueo de capitales”. La creación del Sistema Único ha seguido un proceso acelerado. Fue presentado por el Órgano Ejecutivo a la Asamblea Nacional el 12 de diciembre de 2019. Fue aprobado en la Asamblea Nacional el 19 de diciembre de 2019, en una semana. Se hicieron cambios específicos, y la versión final fue aprobada el 17 de marzo de 2020. El nuevo Sistema Único se limita a la información sobre los beneficiarios finales de las personas jurídicas en las que un abogado panameño, o una firma de abogados panameña, presta el servicio de agente residente. Se refiere a la sociedad anónima panameña, que es el tipo de empresa que requiere un agente residente. La Fundación de Interés Privado Panameña también está incluida en la nueva regulación del Sistema Único, ya que es una entidad legal y tiene un agente residente. Los fideicomisos no son entidades legales, aún cuando tengan un agente residente, por lo que no entran en el ámbito de la nueva ley. El cómo. El registro panameño es privado. Sólo las autoridades indicadas en la ley pueden obtener información de este. El acceso a este nuevo registro privado está limitado a la Autoridad Competente. La Autoridad Competente está compuesta por 5 entidades: 1. La Superintendencia de Entidades No Financieras, 2. la Unidad de Análisis Financiero para la Prevención del Blanqueo de Capitales, 3. el Ministerio Público, 4. el Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas de Panamá y 5. cualquier otra institución u organismo del Gobierno Nacional al que se le atribuya competencia en la prevención del lavado de dinero. Es interesante señalar que el Órgano Judicial, con sus diversas instancias incluyendo la Corte Suprema de Justicia o los tribunales inferiores, no está incluido como Autoridad Competente. Por ejemplo, en los procedimientos civiles en los que una parte requiere saber quién es el beneficiario final de una corporación o fundación de interés privado, un juez no estará facultado para obtener dicha información. Esto puede afectar a la correcta administración de la justicia. Además, los organismos administrativos que se ocupan, por ejemplo, de la contratación pública, no tienen acceso al registro. No se considera ni se utiliza el aspecto de la prevención para reducir al mínimo la corrupción. El cuándo. La nueva ley es un avance formal que implica orden y la búsqueda de un mejor manejo de la información, hasta ahora dispersa y llevada de manera variada por los agentes residentes. Sin embargo, hasta el momento, el registro no ha sido creado y no está operativo. La pandemia ha complicado su creación y puesta en marcha. La historia del progreso normativo panameño muestra que a veces se aprueban formalmente normas más modernas, actualizadas y exhaustivas que las de otras jurisdicciones, pero su aplicación o cumplimiento suele ser deficiente o inexistente. Después de su pronta creación, los elementos más importantes para asegurar que el nuevo registro de beneficiarios finales del Sistema Único funcione o no, se relacionan directamente con dos aspectos, el cumplimiento de la provisión de información inicial y, sobre todo, la realización de las actualizaciones necesarias en forma oportuna. Es importante saber cómo lo están haciendo otras jurisdicciones. A esto se referirá Jaime Chavez Alor, el próximo orador. ¿Y si Panamá no cumple? Los riesgos para Panamá por no implementar pronto en práctica el registro de beneficiarios finales es permanecer en la lista de países con deficiencias en la lucha contra el lavado de dinero, del Grupo de Acción Financiera Internacional. (GAFI) De acuerdo con la ley aprobada en marzo de 2020 y aún pendiente de mayor desarrollo por vía de su reglamentación, a partir de la creación del Sistema Único los agentes residentes deberán proceder a la inscripción de las sociedades y fundaciones privadas como registrantes, así como a la captura de la información requerida para cada persona jurídica constituida o registrada vigente, dentro de los 6 meses siguientes a la notificación hecha por la Superintendencia de Sujetos No Financieros en medios de comunicación de circulación nacional. Esto no ha ocurrido aún. La pandemia ha complicado los esfuerzos. El 23 de octubre de 2020 el GAFI dio la opción de no informar a las jurisdicciones identificadas públicamente como deficientes, en la reunión de octubre de 2020, dado su enfoque en abordar el impacto de la pandemia de COVID-19. Los siguientes países optaron por informar: Albania, Botswana, Camboya, Ghana, Mauricio, Pakistán y Zimbabwe. Los siguientes países aplazaron su presentación de informes: Barbados, Jamaica, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Panamá y Uganda. Otra jurisdicción está enviando el mensaje de que están dispuestos a ir más lejos. Las Islas Vírgenes Británicas (BVI) han anunciado que tendrán un registro público de beneficiarios finales para 2023. Panamá tiene que considerar esto. 29 de junio de 2020. El gobierno de las Bahamas estaba presionando al GAFI para que acordara realizar una visita in situ antes de su sesión plenaria de octubre, según el Fiscal General Carl Bethel. 30 de noviembre de 2020. NASSAU, BAHAMAS – El GAFI ha concluido su visita in situ a las Bahamas, que ahora esperará sus recomendaciones sobre la cuestión de la exclusión de la “Lista gris” del GAFI. |

| Vea el artículo del blog del Dr. Barsallo aquí: http://barsallocarlos.blogspot.com/2020/01/panama-registro-privado-y-unico-de_39.html?m=1 |

|

NOWHERE TO HIDE: |

| See Dr. Barsallo’s blog article here: http://barsallocarlos.blogspot.com/2020/01/panama-registro-privado-y-unico-de_39.html?m=1 |